The Rolling Plains remain one of Texas’ last refuges for wild bobwhite and scaled quail, yet even our strongholds aren’t immune to fragmentation. Over the past century, much of the region’s prairie‑shrub mosaic has been converted to Bermudagrass pastures, monoculture crops and fenced brush clearings. These changes have turned formerly contiguous quail habitat into isolated “islands,” which scientists call habitat fragmentation.

Fragmentation reduces the size and increases the isolation of remaining habitat patches. For bobwhites, the consequences include higher predation risk, reduced immigration and gene flow, smaller coveys and greater susceptibility to local extinction. Data from Georgia’s Bobwhite Quail Initiative show that landscapes with large, closely spaced habitat fragments support much higher quail densities than landscapes with small, widely separated patches. Similar patterns have been observed in the Rolling Plains: researchers at Texas A&M–Kingsville found that scaled quail will roam over miles of contiguous habitat but avoid crossing non‑native grasslands more than 200 yards wide. Even seemingly suitable 300‑acre patches remained unoccupied if they were isolated from larger parcels. This explains why some historic ranches that once teemed with quail are now devoid of quail despite active management.

How much habitat is needed? Oklahoma State University biologists note that viable bobwhite populations require large tracts—around 5,000 contiguous acres—because small “islands” of habitat (e.g., 160 acres) surrounded by poor habitat are not viable. In Louisiana, translocation guidelines developed for the National Bobwhite Conservation Initiative recommend creating at least 600 hectares (≈1,500 acres) of suitable, connected habitat before bringing in birds. These benchmarks underscore that restoring habitat adjacent to existing strongholds is more effective than creating isolated patches.

What about moving birds? Translocation can jump‑start extirpated populations, but it is not a panacea. The Louisiana recovery plan warns that habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation must be addressed first. Recent Tall Timbers research notes that successful translocation requires far more than “moving birds”—landowners must commit to prescribed fire, timber management and predator control, and even then, the natural response of local quail often renders translocation unnecessary. There is still uncertainty regarding the minimum number of quail needed to establish a viable population, how many acres are adequate and how to define success. Each property differs in habitat quality, predator pressure and landscape context, so a one‑size‑fits‑all prescription doesn’t exist.

For landowners and managers in the Rolling Plains, the take‑home message is clear: prioritize habitat restoration that expands or links existing quail strongholds. Work with neighbors to create contiguous grassland‑forb complexes and use hedgerows or rights‑of‑way as corridors. Maintain native shrub corridors, avoid planting wide strips of non‑native grasses that act as barriers and integrate prescribed fire and grazing to keep habitats diverse. By focusing efforts near current quail nuclei, we can strengthen metapopulations and reduce the need for risky, costly translocation. – by Dr. Ryan O’Shaughnessy

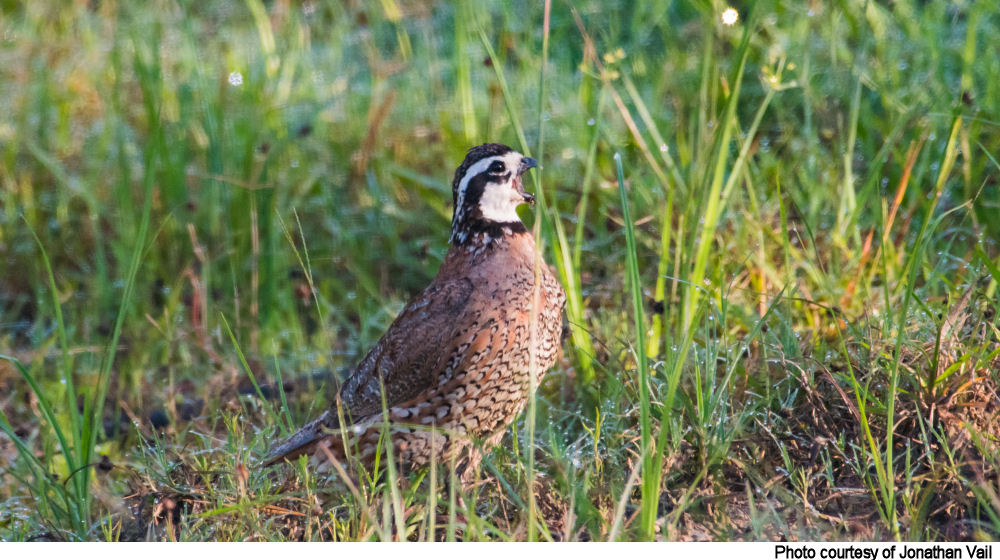

Figure 1: The Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch can be seen in the image surrounded by row-crop agriculture.