FAQQ

(Frequently Asked Quail Questions)

(Frequently Asked Quail Questions)

Q: What kinds of diseases are quail susceptible too?

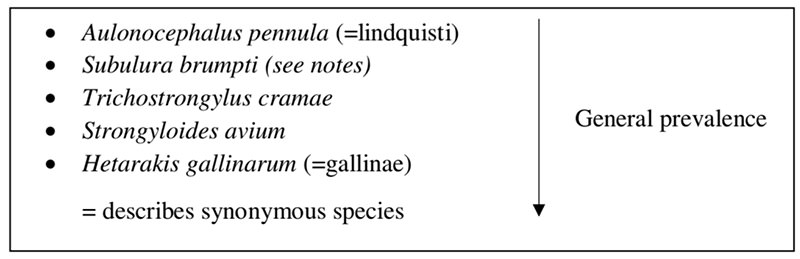

A: Quail, like all animals including humans, are susceptible to a number of different diseases (including parasites). Much of the current research on disease susceptibility actually comes from the poultry industry using pen-raised bobwhites. Thus, for some diseases quail are known to be susceptible, but there is limited data on the prevalence of the disease in wild populations. Similarly, some diseases we know to be highly lethal to pen-raised birds, but have only been documented in wild birds through the presence of antibodies (i.e. the bird was exposed to the pathogen at some point in its life, but is not actively infected) versus an active infection. See the table below for a broad overview of the types of diseases and parasites that can infect quail. For an in depth discussion I recommend the chapter titled “Diseases and Parasites of Texas Quails” by Markus Peterson in the book, Texas Quails.

Q: What are the most common diseases of quail?

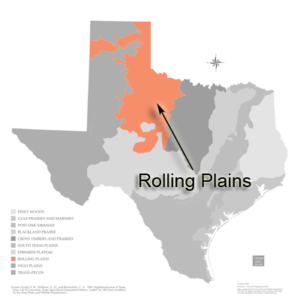

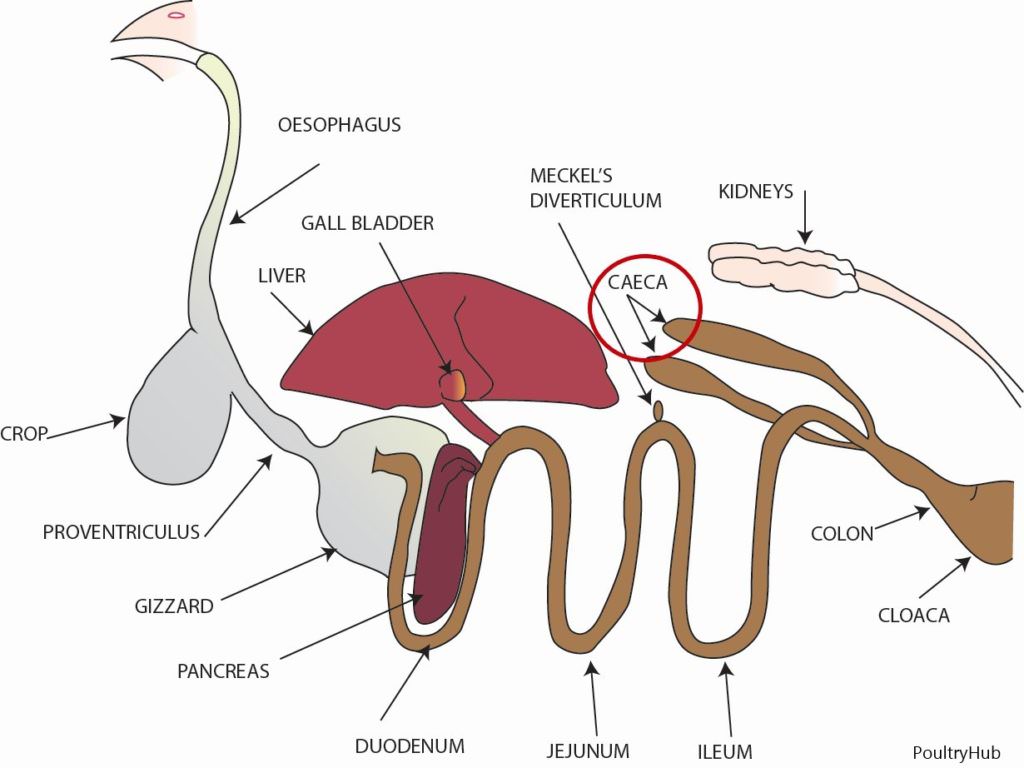

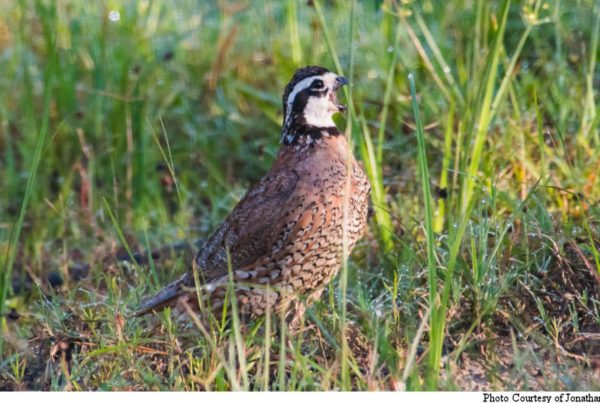

A: Overall in the current state of disease research, the internal worm parasites are the most commonly documented diseases of quail (although these research results come with the caveat that these parasites are also looked for more frequently than other microorganisms such as viruses, bacteria, and protozoans). One cecal worm in particular, Aulonocephalus pennula, has been found at infection rates of up to 90% in a single population. This cecal worm has also been found almost ubiquitously in populations across Texas in both bobwhites and scaled (blue) quail. Despite this potential harmful effects on individual birds or population level effects are still unknown. Eye worms, Oxyspirura petrowi, are also commonly found throughout the Rolling Plains ecoregion with infection rates up to 80% (See Eye worm FAQQ page). Another common pathogen we discovered during sample for Operation Idiopathic Decline, was coccidia, the causative disease agent in coccidiosis, with infection rates of approximately 50% across the Rolling Plains. Hippoboscid flies, which can transmit avian malaria, are commonly found on scaled (blue) quail in the western Edwards Plateau and Trans-Pecos, however the rate of avian malaria infections in these areas is unknown.

Q: Could disease affect population numbers?

A: The short answer is “yes,” but it has not been documented (nor researched in quail, yet). The best example of a disease or parasite regulating a gamebird population is in Scotland with red grouse and a pathogenic cecal worm (Trichstrogylus tenuis). What researchers found was that the higher the infection of cecal worms a grouse harbored the lower it’s probability of reproducing that year. In that way, populations with higher infection rates overall were raising fewer chicks and thus declining in population size. Researchers experimentally proved that by eliminating the cecal worm they could boost reproduction in these populations, thereby taking the “bust” years out the of the annual population cycle. Our ongoing research with eyeworms and cecal worms will be experimental tests of the red grouse hypothesis.

When considering the potential impacts of a supplemental feeding management plan, it is important to consider that increased predation risk could manifest in two areas of a quail’s life cycle: lower nest survival or lower adult quail survival.

Q: Does supplemental feeding increase nest predation?

A: It can. Supplemental feed concentrates mammalian predators, such as raccoons, skunks, or hogs, into a small location. These predators are very efficient at finding nests through their sense of smell and, although they are not coming to the location in search of nests, they come across more nests just by happenstance because of the predator concentration in the area. Research indicates that a supplemental feeding location can impact survival rates of nests within a radius of at least 400 yards. Depending on the density of feeders on a property, overall impacts to nest survival may be negligible or significant. Another factor to consider is that supplemental feeding may increase survival of nest predators thereby increasing the overall predator population and thus, predation pressure on nesting quail.

Q: Does supplemental feeding increase predation on adult quail?

A: Maybe. There is no consensus in the scientific literature on this question. Studies have found that supplemental feeding targeted for quail has increased survival, decreased survival, or had no effect (sometimes researchers found contrasting results between years on the same site within the same study). However, there are some emerging patterns and the differences in results likely lie in the implementation of the feeding programs and the background environmental factors. Biologists do agree on the mechanism through which feeding may predispose adult quail to predation. When quail are drawn to a food source they become predictable to predators (i.e. likely hawks or bobcats in this situation) and are often exposed making them vulnerable. Feeding programs that minimize the concentration and/or exposure of quail are more likely to have the intended benefits, such as broadcast feeding (see below).

Q: What are best management practices to minimize predation risk on quail nests near feeders?

A: The easiest way to minimize predation risk on nests is to simply not feed during nesting season, April through August. If you would like to provide feed or are feeding for other species, consider locating feeders in areas that are not prime nesting habitat. Trapping for small mammalian predators may be another option to minimize predation impacts, but keep in mind that trapping programs are often ineffective. Trapping or other forms of lethal control must be intensive, regular, and cover a large area to have the desired effect.

Q: What are best management practices to minimize predation risk on adult quail as a result of supplemental feeding?

A: When developing a supplemental feeding program care should be taken to minimize the concentration of quail and their exposure to predation (both from the ground and from the air).

One method is to broadcast feed or scatter feed widely in areas with brush cover. Managers can distribute feed throughout a pasture (i.e. off road) or distribute feed in to the brush adjacent to the road. This method minimizes quail congregation and allows quail to feed without leaving cover. Feeding quail directly in the road may leave them vulnerable to avian predators. There could be ancillary benefits to broadcast feeding in the brush as well. Researchers at Tall Timbers found that broadcast feeding accomplished their intended goals of boosting quail survival, but in an indirect manner. Broadcast feeding increased the rodent population which then acted as a buffer species (i.e. predators consumed more small mammals thereby easing predation pressure on quail).

On RPQRR we make use of Currie or barrel quail feeders (see supplemental feeding FAQQ) for supplemental feeding. However, our barrels are carefully concealed to help minimize predation risk. When placing feed stations on the landscape try to find dense brush cover that will help conceal quail from predators. Placing the feeder itself in concealing brush is important as well as making sure that there is escape cover in close proximity surrounding the feeder. Quail make use of this cover as they journey to feed in the mornings and evenings. It also provides refuge from avian predators if they are detected at the feeder.

Q: Can management mitigate some of the predation risks from supplemental feeding of supplemental feeding?

Q: Can management mitigate some of the predation risks from supplemental feeding of supplemental feeding?

A: Yes! Supplemental feeding may concentrate potential predators of quail, especially raccoons. Such feeding sites can be used to increase efficiency of raccoon-reducation attempts. Placing 2-4 “cage traps” and several “dog-proof” traps near feeders on a pewriodical basis can be used to reduce raccoons. Use game cameras to provide surveillance of your quail (or deer) feeders to indicate if trapping would be warranted.

Q: Is it better to restock with pen-raised or wild-caught translocated birds?

A: There are challenges and drawbacks associated with both. In general pen-raised birds are cheaper and easier to obtain, but wholly ineffective at reestablishing quail populations beyond a simple “put and take” model (i.e. releasing immediately prior to shooting). For more discussion on pen-raised birds refer to the FAQQ. For the purpose of this FAQQ we will focus on wild-caught translocated birds. Recent research on RPQRR and elsewhere has shown that translocation can be effective. However, currently more research is needed to determine what factors contribute to translocation success in quails and all past translocations of quail in Texas have been research driven (in contrast to management driven).

Q: Specifically, what is translocation?

A: Translocation is the intentional capture, movement, and release of wildlife from one site to another. Translocation can be used to establish populations in new ranges where they previously did not exist, to reestablish populations where they have gone extinct, or augment populations that are dwindling. Historically, translocation has been used to establish many game species outside of their range in North America (e.g. Brook and rainbow trout in the west, pheasants throughout the Mid-west, or California quail in Montana). However, given the potential for far-reaching, disastrous ecological impacts that many historical introductions have demonstrated, the establishment of species outside of their native range is frowned upon today. Most commonly today, translocations are used to reestablish wildlife populations within native ranges. This has successfully been used for many game species in Texas, including wild turkeys and white-tailed deer. Outside of Texas, populations of popular gamebird species such as sharp-tailed grouse, sage grouse, and mountain quail have been the beneficiaries of translocation efforts. Less commonly, translocation can be used to augment declining populations of wildlife before they go extinct. Although it is less commonly used, augmentation has potential to be more successful than reestablishing populations from zero because newly released animals are able to observe conspecifics (i.e., other members of the same species) and potentially fewer translocated animals will be needed to make an impact.

Q: What is a TTT permit?

A: TTT stands for trap, transport, and transplant. As the state game agency, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) administers all TTT operations. A TTT permit from TPWD “authorizes certain game animals to be trapped from properties with excess population numbers and relocated to properties with sufficient habitat to support the additional animals” (see TPWD’s TTT permit page.

Q: Can I get a TTT permit for quail?

A: Maybe. Currently, there have not been any TTT permits granted by TPWD to private landowners for quail, but given the recent research demonstrating the feasibility of translocation and mounting national interest in translocation as a tool to restore wild quail populations there may be TTTs granted for quail in the future. To get a better understanding of your eligibility review TPWD’s The Upland Game Bird Management Handbook for Texas Landowers.

Q: What is the minimum property size for a TTT?

A: The minimum property size considered is 1,000 acres of habitat. The preferred property size is 3,500 acres of habitat. It is worth noting that these acres to do have to be owned by the same individual, thus conservation cooperatives or other groups of landowners that are made up of contiguous properties (i.e. share fence lines) may be eligible to apply jointly.

Q: Where can I find a TTT conservation partner?

A: Right here! RPQRF is willing to help facilitate official TTT efforts for private landowners. We have the infrastructure and knowledgeable staff available to help at any stage of the TTT planning and implementation process.

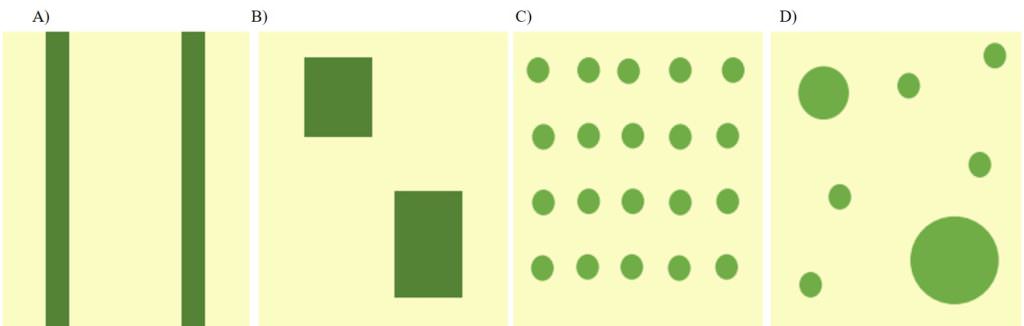

Q: What is the Softball Habitat Evaluation Technique?

A: Developed by Dr. Rollins and abbreviate SHET for short (be careful with your enunciation!), this technique is a good way to visualize and communicate what habitat for quail should look like. It is based on the premise that there are many corollaries between the game of softball and the realities of being a quail and creating quail habitat. It is not a formal evaluation, but this analogy can help the land owner or land manager visualize what good quality quail habitat looks like and what quail need. Most people are familiar with the game of softball, but may have a difficult time visualizing what a biologist is talking about when they say that you need a mosaic of different land covers to provide quail habitat. You may even want to use this technique to communicate with contractors to help them visualize what you want to achieve with your habitat management.

Q: What are the corollaries between the game of softball and quail?

A: A quail is about the same size as a softball and, similar to a softball on the field, whenever either is exposed something or someone is trying to catch it or whack it. If you examine a typical slow-pitch softball, you may see the words “restricted flight.” It is by design that you cannot hit a softball as far as a baseball. Quail also have “restricted flight”—their light-colored breast muscle prohibits them from flying as far as some other birds (e.g., the dark breast muscle of a mourning dove). Although quail can fly quickly, they are only able to fly a short distance before seeking cover. As such, a quail needs escape cover, or a quail house, about every softball throw apart. If you can visualize how far you can throw a softball, you’ll understand about how far apart escape cover should be on the landscape to make good quail habitat. In other words, you should be able to throw a softball from one brush covert (“quail house)” to another across the pasture.

The game of softball can also be used to visual what good quality nesting cover should look like. Quail need a high density of bunchgrasses (> 250 clumps/acre) to provide nesting cover or about 25-30 nesting sites in the area of the infield. Ideally, those bunchgrasses should be about the size of home plate and prickly pear should be about the size of both batter’s boxes to provide nesting cover.

If you pitch the softball (about 46 ft) it should roll a short distance and then be obscured by the grass cover or other herbaceous cover on the ground. This indicates that the ground cover is thick enough to provide visual protection from predators, but not too thick to impede movement by ground-dwelling quail. If the ball “sticks” rather than bounces after you pitch it, this indicates that the ground cover may be too thick. If the ball is still visible from that distance, this indicates that you may need to reduce your stocking rate of livestock to provide sufficient ground cover.

Other similarities between bobwhites and softball include:

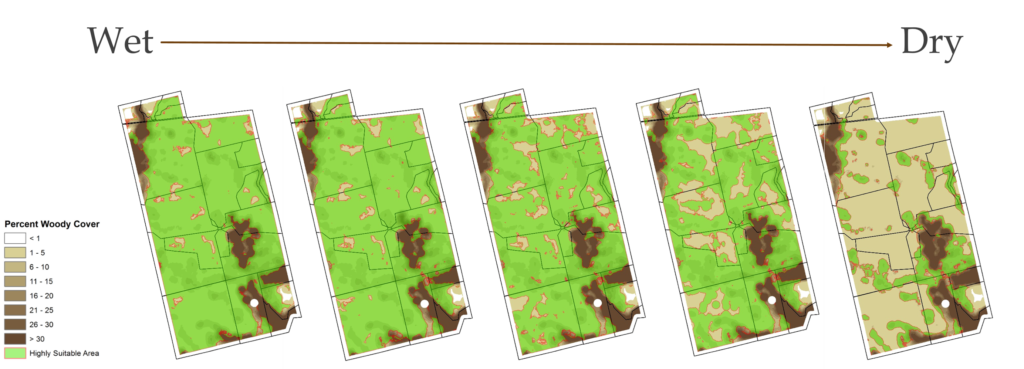

The Rolling Plains encompasses approximately 24 million acres and is occupied by bobwhite and scaled quail. The Rolling Plains of Texas hosts the highest long-term mean of bobwhite abundance across the state, according to Texas Parks and Wildlife annual roadside surveys. During good years, hunters can expect a bird per acre, or more, on managed areas. Scaled quail are also very abundant in certain parts of this region (mostly western). Like most quail populations in semi-arid ecoregions of Texas, populations for both quail species fluctuate greatly by site and year. For long-term trends and annual forecast for the Rolling Plains, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/rolling_plains/

The Rolling Plains encompasses approximately 24 million acres and is occupied by bobwhite and scaled quail. The Rolling Plains of Texas hosts the highest long-term mean of bobwhite abundance across the state, according to Texas Parks and Wildlife annual roadside surveys. During good years, hunters can expect a bird per acre, or more, on managed areas. Scaled quail are also very abundant in certain parts of this region (mostly western). Like most quail populations in semi-arid ecoregions of Texas, populations for both quail species fluctuate greatly by site and year. For long-term trends and annual forecast for the Rolling Plains, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/rolling_plains/ Situated north and west of the Rolling Plains, the High Plains (ca. 20 million acres) of Texas also hosts good populations of both bobwhite scaled quail. Thus, the High Plains offers another great destination for hunting for either species. Good hunting can afford a bird per acre during good years. Like the Rolling Plains, however, populations fluctuate greatly depending on habitat quality and rainfall each year. For long-term trends and annual forecast for the High Plains, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/high_plains/

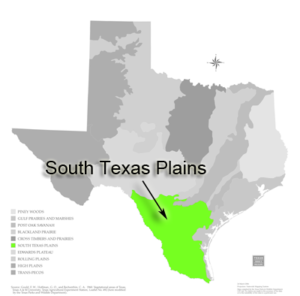

Situated north and west of the Rolling Plains, the High Plains (ca. 20 million acres) of Texas also hosts good populations of both bobwhite scaled quail. Thus, the High Plains offers another great destination for hunting for either species. Good hunting can afford a bird per acre during good years. Like the Rolling Plains, however, populations fluctuate greatly depending on habitat quality and rainfall each year. For long-term trends and annual forecast for the High Plains, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/high_plains/ The South Texas Plains (ca. 20 million acres) is another iconic destination for hunting wild quail. Populations of bobwhite are on par with the Rolling Plains and High Plains, but scaled quail populations tend to be more scattered and concentrated in certain areas. For long-term trends and annual forecast for the South Texas Plains, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/south_texas_plains/

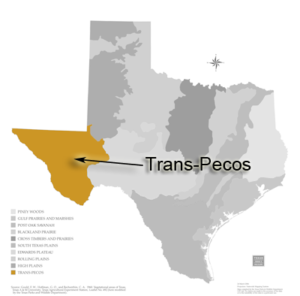

The South Texas Plains (ca. 20 million acres) is another iconic destination for hunting wild quail. Populations of bobwhite are on par with the Rolling Plains and High Plains, but scaled quail populations tend to be more scattered and concentrated in certain areas. For long-term trends and annual forecast for the South Texas Plains, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/south_texas_plains/ The Trans Pecos ecoregion is roughly 19 million acres and home to all 4 native species of quail in Texas– Bobwhite, Scaled, Gambel’s, and Montezuma quail. Bobwhite are not common west of the Pecos River and are occasionally only found in this region at low densities. Scaled quail are the most popular game species in this region. For long-term trends and forecasts for scaled quail, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/trans_pecos/

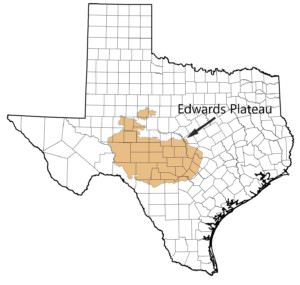

The Trans Pecos ecoregion is roughly 19 million acres and home to all 4 native species of quail in Texas– Bobwhite, Scaled, Gambel’s, and Montezuma quail. Bobwhite are not common west of the Pecos River and are occasionally only found in this region at low densities. Scaled quail are the most popular game species in this region. For long-term trends and forecasts for scaled quail, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/trans_pecos/ The Edwards Plateau hosts 3 of the 4 native quail species in Texas– bobwhite, scaled, and Montezuma quail. Bobwhite populations in this regions offer fair to good hunting, where habitat exists and during favorable years. Scaled quail may also provide hunting opportunity in certain parts of the region. Populations of Montezuma quail are known to occur in Edwards, Val Verde, and Kinney counties, but similar to other species have suffered population declines due to loss of habitat. For more information on long-term trends on bobwhite and scaled quail in the Edwards Plateau, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/edwards_plateau/

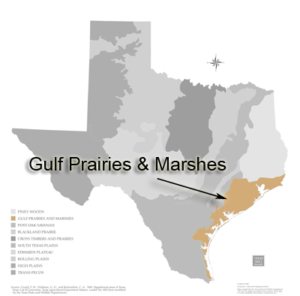

The Edwards Plateau hosts 3 of the 4 native quail species in Texas– bobwhite, scaled, and Montezuma quail. Bobwhite populations in this regions offer fair to good hunting, where habitat exists and during favorable years. Scaled quail may also provide hunting opportunity in certain parts of the region. Populations of Montezuma quail are known to occur in Edwards, Val Verde, and Kinney counties, but similar to other species have suffered population declines due to loss of habitat. For more information on long-term trends on bobwhite and scaled quail in the Edwards Plateau, see: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/edwards_plateau/ The Gulf Coast Prairies and Marshes encompass about 24 million acres bordering the gulf coast. The largest threat to bobwhite population in this area may be the conversion of native rangelands to improved pastures for cattle and intensification of other agricultural practices. Bobwhite hunting can be good (upwards to a bird / acre) on areas managing for quail during favorable years. For more information on long-term trends and forecasts in this region, see:

The Gulf Coast Prairies and Marshes encompass about 24 million acres bordering the gulf coast. The largest threat to bobwhite population in this area may be the conversion of native rangelands to improved pastures for cattle and intensification of other agricultural practices. Bobwhite hunting can be good (upwards to a bird / acre) on areas managing for quail during favorable years. For more information on long-term trends and forecasts in this region, see: The Cross Timbers and Prairies historically afforded great bobwhite hunting, but general population trends have descended rapidly since 1994. Rainfall during the early 1990s in the region was average to above average and does not explain the steep declines. Chronic habitat loss and fragmentation due to changes in land use has been considered the main cause of the decline. Like many regions, pockets of well-managed habitat still offer fair to good wild bobwhite hunting opportunities during favorable years. In these situations, one could expect a property to approach a bird per acre, but relative few areas host these bird densities.

The Cross Timbers and Prairies historically afforded great bobwhite hunting, but general population trends have descended rapidly since 1994. Rainfall during the early 1990s in the region was average to above average and does not explain the steep declines. Chronic habitat loss and fragmentation due to changes in land use has been considered the main cause of the decline. Like many regions, pockets of well-managed habitat still offer fair to good wild bobwhite hunting opportunities during favorable years. In these situations, one could expect a property to approach a bird per acre, but relative few areas host these bird densities. The East Texas Piney Woods once offered good hunting for bobwhite in the state, but wild populations are sparse and-or extirpated across most of the region, today. Wild, huntable populations are extremely rare. Roadside surveys initiated by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in 1976 were discontinued in this region in 1988. The main cause of the decline in this region is attributed to habitat loss through changes in land use. Most notable land use changes have been the conversion of native forests to commercial timber operations, planting exotic grasses for grazing, and suppression of fire on natural areas.

The East Texas Piney Woods once offered good hunting for bobwhite in the state, but wild populations are sparse and-or extirpated across most of the region, today. Wild, huntable populations are extremely rare. Roadside surveys initiated by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in 1976 were discontinued in this region in 1988. The main cause of the decline in this region is attributed to habitat loss through changes in land use. Most notable land use changes have been the conversion of native forests to commercial timber operations, planting exotic grasses for grazing, and suppression of fire on natural areas. The Blackland Prairies ecoregion of Texas historically hosted good populations of bobwhite and offered decent hunting opportunities. Similar to the East Texas Piney Woods and Post Oak Savannah ecoregions, bobwhite populations are sparse and-or extirpated across most of the region. Likewise, roadside surveys initiated by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in 1976 were discontinued in this region in 1988. The main cause of the decline in this region is also attributed to habitat loss through changes in land use. Conversion of native range to exotic grasses for grazing and hay production have been one of the most influential land use changes in this region. Urbanization has also been a large source of habitat loss for this region.

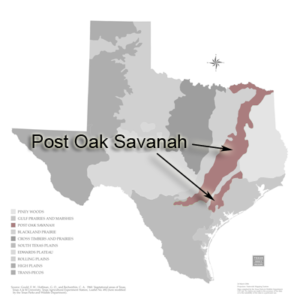

The Blackland Prairies ecoregion of Texas historically hosted good populations of bobwhite and offered decent hunting opportunities. Similar to the East Texas Piney Woods and Post Oak Savannah ecoregions, bobwhite populations are sparse and-or extirpated across most of the region. Likewise, roadside surveys initiated by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in 1976 were discontinued in this region in 1988. The main cause of the decline in this region is also attributed to habitat loss through changes in land use. Conversion of native range to exotic grasses for grazing and hay production have been one of the most influential land use changes in this region. Urbanization has also been a large source of habitat loss for this region. The Post Oak Savannah stretches from Northeast Texas to Southcentral Texas across about 8.5 million acres. Because of low bobwhite populations in the area, roadside surveys initiated by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in 1976 were discontinued in this region in 1988. Historic bobwhite populations in this area were fair, but never considered among the prime bobwhite regions in the state. Roadside surveys during 1976–1987 only averaged about 5 birds per route, but some areas offered good hunting opportunities. Small, isolated populations of wild bobwhite currently exist, with few hunting opportunities. Conversion of native range to exotic grasses for grazing and hay production have been one of the most influential land use changes in this region. Urbanization is also a large source of habitat loss in this region.

The Post Oak Savannah stretches from Northeast Texas to Southcentral Texas across about 8.5 million acres. Because of low bobwhite populations in the area, roadside surveys initiated by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in 1976 were discontinued in this region in 1988. Historic bobwhite populations in this area were fair, but never considered among the prime bobwhite regions in the state. Roadside surveys during 1976–1987 only averaged about 5 birds per route, but some areas offered good hunting opportunities. Small, isolated populations of wild bobwhite currently exist, with few hunting opportunities. Conversion of native range to exotic grasses for grazing and hay production have been one of the most influential land use changes in this region. Urbanization is also a large source of habitat loss in this region. Rice breast is a term hunters often use to describe white specks in meat of harvested game. Unlike rice breast in ducks, which is caused by a protozoan pathogen, rice breast in quail is caused by larval nematodes (i.e., round worms) of the genus Physaloptera. The particular species which occurs in quails is unknown because morphological characteristics of the worm at this stage of its life cycle are not reliable metrics for identification. It is likely that the species occurring in quails is Physaloptera rara, given its prevalence in mammals where quail infections typically occur. The white specs surrounding the encysted worms are granulomas.

Rice breast is a term hunters often use to describe white specks in meat of harvested game. Unlike rice breast in ducks, which is caused by a protozoan pathogen, rice breast in quail is caused by larval nematodes (i.e., round worms) of the genus Physaloptera. The particular species which occurs in quails is unknown because morphological characteristics of the worm at this stage of its life cycle are not reliable metrics for identification. It is likely that the species occurring in quails is Physaloptera rara, given its prevalence in mammals where quail infections typically occur. The white specs surrounding the encysted worms are granulomas. Q: How do quail become infected with Physaloptera?

Q: How do quail become infected with Physaloptera?

For an overview of brush sculpting for various plant communities and species of game animals, see the 1997 symposia proceedings Brush Sculptors: Innovations for Tailoring Brushy Rangelands to Enhance Wildlife Habitat and Recreational Value available: https://texnat.tamu.edu/library/symposia/brush-sculptors-innovations-for-tailoring-brushy-rangelands-to-enhance-wildlife-habitat-and-recreational-value/ .

Bobwhites are one of the most studied game bird in the world, and many books have been written about their biology, management, hunting culture and strategies. The following are brief synopses of books recommended for further study. Prices are based on those set by the publisher.

|

Name: Beef, Brush, and Bobwhites: Quail Management in Cattle Country Authors: Fidel Hernández and Fred S. Guthery Publisher: Texas A&M Press Year: 2012 Price: $25 Beef, Brush, and Bobwhites is a prime, go–to general ecology and management reference for bobwhite enthusiasts in semi-arid rangelands of Texas, namely South Texas and the Rolling Plains. Easy to read and equally apt for the coffee table or as a field reference, pp. 244. |

|

Name: Texas Bobwhites: A Guide to Their Foods and Habitat Management Authors: Jon A. Larson, Timothy E. Fulbright, Leonard A. Brennan, Fidel Hernández, and Fred C. Bryant Publisher: University of Texas Press Year: 2010 Price: $25 Texas Bobwhites primarily highlights food items and provides high-quality images of plants and seeds found in the diet of bobwhites in Texas. The latter part of the book focuses on general ecology and habitat management, pp. 280. |

|

Name: On Bobwhites

Authors: Fred S. Guthery Publisher: Texas A&M Press Year: 2000 Price: $23 On Bobwhites is an all-around reference for bobwhite ecology and general management. Though the author uses many Texas references, the book is fairly well-rounded and may be an appropriate reference for other parts of the bobwhite range, as well, pp. 213. |

|

Name: Texas Quails: Ecology and Management, First Edition

Editor: Leonard A. Brennan Publisher: Texas A&M Press Year: 2007 Price: $40 Texas Quails is a textbook-style compendium of research and management information for all 4 native quail species in Texas. The book is outlined in 3 section:species ecology, populations and management by ecoregion, and culture/heritage of Texas quail hunting. Written by multiple quail authorities and edited by Leonard Brennan, Texas Quails offers one of the most diverse, yet concise references available for both the technical and popular community. The first edition (pp.491) was released in 2007 and a second edition has been slated for release within the next few years (ca. 2021). |

|

Name: Tall Timbers’ Bobwhite Quail Management Handbook

Editors: William E. Palmer and Clay Sisson Publisher: Tall Timbers Press Year: 2017 Price: $30 The Tall Timbers’ Bobwhite Quail Management Handbook is a reference for those interested in or managing bobwhite populations in the Southeastern US (forested ecosystems). The Tall Timbers’ Bobwhite Quail Management Handbook may be paralleled to Beef, Brush, and Bobwhites, for forested habitats. For those managing bobwhite in East Texas, this book may be the only reference that comprehensively, yet concisely addresses management in your area, pp. 160. |

|

Name: Range Plants of North Central Texas: A Land Users Guide to Their Identification, Value, and Management

Author: Ricky J. Linex Publisher: Natural Resources Conservation Service Year: 2014 Price: $25 Range Plants of North Central Texasis a book written with quail in mind and published by funds made available almost exclusively by quail fanatics (including RPQRF). Range Plants of North Central Texas covers 324 plants (160 forbs, 59 grasses, and 105 woodies), most of which can be found in many areas of the state, not just North Texas. The reference offers nearly 1,500 high–quality photos of plants and seeds to help in identification and discusses management and wildlife values for each plant, pp. 345. |

|

Name: Technology of Bobwhite Management: The Theory Behind the Practice

Author: Fred. S. Guthery Publisher: Wiley- Blackwell Year: 2002 Price: $175 (rare, out of print) Technology of Bobwhite Management is a technical reference which is essentially a concise compendium of peer-reviewed research, primarily from Fred S. Guthery’s career. The resource is not a management guide, but may be more appealing to those in academia. The book is now out of print, and difficult to acquire. If available for purchase, a copy under $100 would be a steal. |

|

Originally published in 1931, The Bobwhite Quail: Its Habits, Preservation, and Increase (pp. 559) by Herbert L. Stoddard is the first book written to comprehensively describe bobwhite life history. According to Google Scholar, this book is the most cited reference in bobwhite literature, being cited nearly 1,000 times. Accordingly, the text has been colloquially deemed“The Bible of Bobwhite Management,” and its author, the “Father of Bobwhite Management.” An original copy of this book can run for hundreds, even thousands of dollars with reprints (into the 1970s) on the lower end of this continuum. Stoddard conducted his research in the Red Hills of Florida and Georgia, and was one of the first to formalize and document the importance of fire for bobwhite in pine ecosystems. In his autobiography, “Memoirs of a Naturalist,” Stoddard goes more into depth on his journey throughout life. |

|

Dan Lay’s quail management handbook (pp. 46) published by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department was first released for East Texas in 1954. The small, pamphlet style publication serves as a management reference for landowners in East Texas and still contains much relevant information. Following Lay’s publication in the 1950s, the Texas Parks and Wildlife released a similar pamphlet (pp. 75) written by A. S. Jackson in 1969, for the West Texas Rolling Plains. Though not extremely comprehensive, these texts are iconic classic bobwhite literature and are still widely cited.

A digital copy for Quail Management Handbook for West Texas Rolling Plains: Download Here. |

|

In 1969, Walter Rosene published his classic text, The Bobwhite Quail: Its Life and Management(pp. 418). Rosene’s style parallels Stoddard’s, but provides are slightly larger geographic extent (to include Alabama and more central ranges) and expands upon Stoddard’s original work, which Rosene makes frequent reference. |

|

The year 1984 brought about 2 seminal bobwhite texts: “Population Ecology of the Bobwhite” (pp. 304) by John Roseberry and Willard Klimstra and “Bobwhites in the Rio Grande Plain of Texas” (pp. 371) by Val Lehmann. Roseberry and Klimstra’s work was based in Illinois and is a comprehensive text on research conducted in the area during the 1950s through 1970s. Bobwhites in the Rio Grande Plain of Texas was the first resource to extensively document bobwhite life history in the semi-arid ecoregion of South Texas. Lehmann makes reference to work in the blackland prairies and gulf coast regions, as well. Data collected for this text were collected from the 1940s to 1970s. |

|

In 1985, the International Quail Foundation released “Bobwhite Thesaurus,” (pp. 306) by Thomas G. Scott. This book is strictly a book of reference- quite literally. Scott developed a bibliography of literature to index all publications prior to 1983. Given the vast amount of literature, this publication’s intent was to index citations to make them more accessible. The book is simply an extensive index of approximately 2,800 citations from 1822–1982, organized by their respective subject-categories. An index of the sort from 1983–present is not available.

|

Q: Are hunting season lengths and bag limits too generous?

A: The hunting season for quails in Texas is currently open from the last Saturday in October to the last Sunday in February. With a daily bag limit of 15 birds and a 4 month season, a hunter could potentially harvest 1,830 quail. On the surface, these numbers are alarming. However, few hunters hunt very many days nor bag their limits on a daily basis. The TPWD sets a generous season length and bag limit so as not to hinder hunter opportunity (thus sales of hunting licenses). The “average” quail hunter in Texas hunts less than 10 days per season and bags less than 3 birds/day.

Q: Who determines harvest regulations for quails in Texas?

A: Hunting regulations are established by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission. The Commission receives input from TPWD biologists periodically according to how quail populations are faring. Biologists conduct annual roadside counts in august over most ecoregions of Texas to monitor quail abundance. See TPWD’s annual quail hunting forecast (https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/planning/quail_forecast/forecast/) for an example of these counts.

Q: Should I be concerned with overharvesting?

A: One should consider two factors when contemplating this issue: scale and time. In general, due to the nature of quail and quail hunting, overharvest is not a management concern, at least not at the state-wide level. At larger scales, quail hunting tends to be “self-regulating”, i.e, during “boom” years hunting efforts are increased and in “bust” years hunting efforts are decreased because of low success. This self-regulating nature may not be applicable to smaller scales, e.g., a quail lease or an individual ranch. When quail abundance is low, e.g., during a drought, any hunting would tend to be more additive, and thus harvest should be monitored more closely.

Q: I’ve heard words like “additive” vs. “compensatory” in discussions regarding harvest management. What do these mean and why are they important?

A: Compensatory loss is that which occurs or would have occurred naturally, e.g., via predators. Additive loss is that loss which would not have occurred naturally, i.e., the mortality is adds to the overall mortality of the population. The time of year in which individual birds are harvested determines how compensatory or additive the loss is to the population. Most quail biologists support the notion that harvest ascribes to an additive-mortality theory. This theory states that harvest is neither 100% compensatory nor 100% additive, but a combination of the two. However, as the season progresses, the percentage of additive loss increases. This is due to the fact that individuals alive in February have a much higher probability of entering breeding season than individuals in November

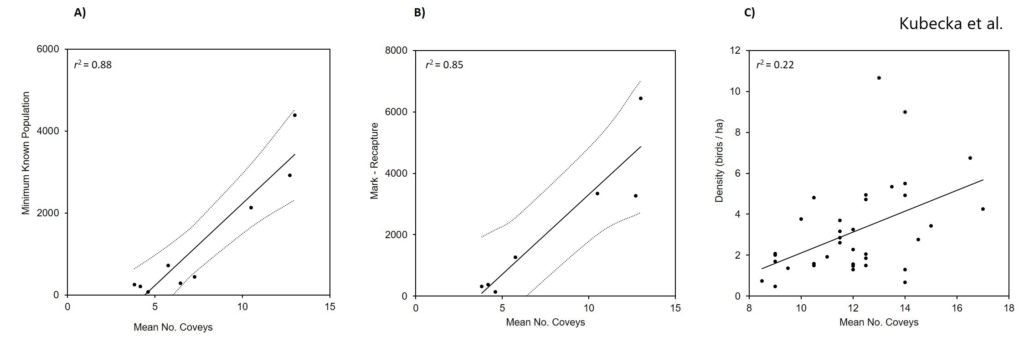

Q: How can I avoid overharvesting?

A: To avoid overharvesting, landowners and ranch managers should come up with responsible harvest quotas. Conducting annual surveys like roadside counts in September is a cost-effective way to monitor quail abundance in the Rolling Plains (see “Counting Quail”). During poor years, hunters on a lease should consider abstaining from late season hunts and voluntarily decreasing daily bag limits to fewer than 6 birds/day.

For those seeking further information on quail habitat management or in developing a quail management plan, several resources exist.

The non-profit organization Quail Forever provides quail management information on their website. They have also recently hired two new Coordinating Wildlife Biologists for the state of Texas “to assist landowners in implementing early successional habitat projects for the benefit of quail and other wildlife.”

Other online resources include the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, the Texas Parks and Wildlife “Quail in Texas” page, and the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service’s “Quail Management” page.

You can also contact your local office of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), your local county Texas Parks and Wildlife Service biologist, or your local county office of AgriLife Extension Service.

If you are willing to do a bit of reading, Beef, Brush, and Bobwhites: Quail Management in Cattle Country by F. Hernandez and F. Guthery, is a great resource for quail managers. Another good book is Texas Quails: Ecology and Management edited by L. A. Brennan and published by the Texas A&M University Press.

Finally, you can contact the Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch at (325)-776-2615.

Hosted by Dr. Dale Rollins and Gary Joiner of Texas Farm Bureau & Sponsored by Gordy and Sons Outfitters.

How to Search for Eyeworms in Quail – Eyeworms (Oxyspirura petrowii) have been identified as possible culprits in the “quail decline” that is occurring in west Texas. Studies confirm they can result in scarring of the cornea and inflammation of the optic nerve, and likely result in decreased vision of quail. As of 2019, the maximum number of eyeworms removed from one bobwhite was 107, and infections of 20 or more eyeworms are common in the Rolling Plains. Eyeworms can be identified in the field with about 80% accuracy (presence/absence) using the Crafton or Newsome techniques (described herein), but accurate counts require dissection of the tissues surrounding the eyeballs. . Watch this video as research assistant Jennifer Newkirk demonstrates the method used to inspect quail for eyeworms.

How to Search for Eyeworms in Quail – Cecal worms (Aulonocephalus pennula) have been implicated as possible culprits in the “quail decline” that is occurring in west Texas. They are found in the lower gut of both bobwhite and scaled quail. They are the most common nematode parasite in quail; we have found over 900 cecal worms in a single bobwhite, and average intensities are commonly over 200 worms/bird. Watch this video as research assistant Jennifer Newkirk demonstrates the method used to inspect quail for cecal worms.

Operation Idiopathic Decline – The role that disease and parasites may play in quail dynamics has been largely ignored since the 1920s. After the (in our opinion) inexplicable decline of quail in the Rolling Plains, the Board of RPQRF “got serious” about disease and funded a comprehensive project dubbed “Operation Idiopathic Decline.” Currently (as of Feb 2014), the RPQRF has invested $3.4 million into this ground-breaking study of disease and parasites. This webisode explains OID in more depth.

Plant succession – Plant succession is the “orderly, predictable process of change in plant communities over time.” A knowledge of plant5 succession is one of the most powerful tools in the managers tool-kit. In this video, Dr. Rollins explains how sucxcession works, and shows how relatively minor changes in the timing of soil disturbance (in this case disking on rangeland) can promote vastly different plant communities. Changes are discussed relative to plant and insect diversity and why this practice is important for quail management.

Sounds quail make – You’re familiar with the iconic ‘poor-bob-white’ whistle and the memories that such a whistle evokes. But did you know that a bobwhite makes over a dozen different “vocalizations?” Here Dr. Dale Rollins, executive director for the RPQRR and a World Quail Calling Champion (2001) does his a capella renditions of various quail calls and related sounds. Researchers and quail managers often base their “quail counts” on various whistles that the quail make. Learning to interpret these calls (and maybe even mimic them!) can give you a better appreciation of “quail talk” and perhaps even make you a more successful quail hunter.

Ragweeds and Quail – Ambrosia is often used to describe the “food of the gods.” A fitting association for quail managers as the Latin name of ragweed is “Ambrosia.” Western ragweed is the plant that earned the dedication of quail hunters as it did the disdain of hay fever sufferers. In most winters it is an important (if not the most important) seed in the bobwhite’s crop. In this webisode, Dr. Rollins compares and contrasts three species of ragweed found on RPQRR.

Quail Research Sites

Recommended Books & Field Guides

Data Sheets

Plant of the Month

Field Day Reports

Other publications

Popular Articles

Journal Articles