“For a Central American dictator he died a natural death—he was shot in the back.” – Will Rogers

Few quail die of old age. Most die before seeing their first birthday. Some meet their death from F-150s, some from 20-gauges. But most meet their demise from the fangs or talons of various predators. Death from above, and death in the tall grass. One’s scourge varies according to season; various “mesocarnivores” (e.g., bobcats, foxes, coyotes, skunks) claim more quail during the summer (e.g., nesting season), while various raptors (e.g., hawks) earn Top Gun during the winter.

This issue of e-Quail examines the impact of predators on RPQRR’s quail population (bobwhites and blues). It’s easy (as quail hunters) to cast a jaundiced eye on our competitors. I Rollins-ize Newton’s 3rd Law of Motion as “to every action there are many reactions, some apparent, others more transparent.” One of the most-cited essays regarding an ecological perspective of predation is Aldo Leopold’s Thinking Like a Mountain (http://www.eco-action.org/dt/thinking.html).

In the context of quail and predation, we should at least aspire to think like a sandhill. We should appreciate how predation (as a selection pressure) has helped shape the behaviors in quail that we admire (e.g., a covey rise). For two relevant articles see Rollins and Carroll (2001; https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers/651/ ) and Rollins (1999; http://texnat.tamu.edu/files/2010/09/page11.pdf ). Also see one of Agrilife’s latest webisodes “Predator Management and Quail”.

Predation and predation management are often (always) controversial. So, in the vernacular of Sgt. Joe Friday (ala Dragnet) here’s what I offer as “just the facts ma’am.” As we enter our 11th year at RPQRR, we’ve begun (and continue) to amass the “facts” of just how multifaceted (hence complex) the quail equation is relative to predation.

Impacts on survival

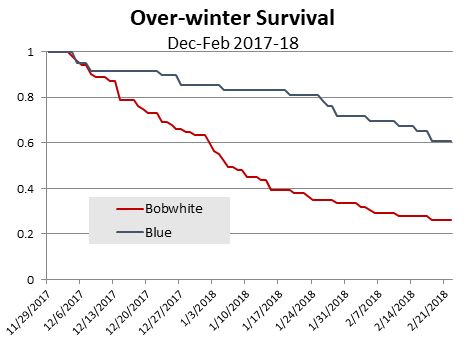

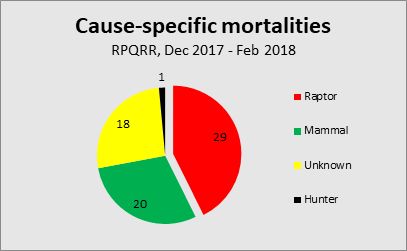

Technicians Carl Underwood, Casey Weissburg, and Trey Johnson contributed to this section on survival and “cause-specific mortality.” Our bobwhites (especially) have had a rough winter survival-wise. When we have a mortality, we inspect the kill site and conduct “Quail CSI”, seeking to determine if the kill was that of a raptor or a mammal. We examine the feather piles, check for teeth marks on the transmitter, and look for other telltale signs (i.e., the presence of a gizzard suggests a bobcat was responsible). Our diagnoses are never certain, but serve as educated guesses. Typically 20-40% of the kills are classified as “unknown” if we’re not comfortable with assigning a specific cause of death.

We’ve experienced 66 mortalities of radio-collared quail since 29 November (57.8%). Interestingly, blues were killed by mammals more often (44%) than by raptors (31%). In contrast, bobwhites were taken by raptors more often (46%) than by mammals (24%), with unknown cause of death contributing 28% of mortalities and hunters 2% (one individual). Whether this is due to choice of habitat or to the habit of Blues to run rather than fly, is difficult to say without additional information about habitat structure and intensive behavioral observation.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for radio-marked bobwhite (n = 69) and blue quail (n = 46) on the RPQRR, Dec 2017 – Feb 2018.

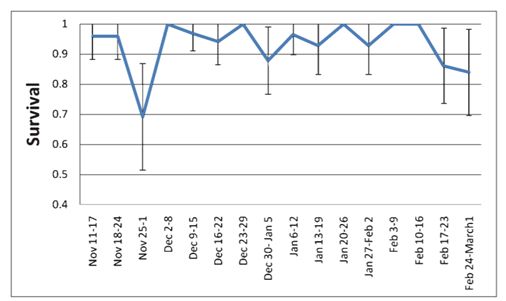

These estimates for winter survival are similar to what we experienced in 2008 (34%) and 2009 (38%) on a ranch adjacent to the RPQRR (Teinert et al. 2009; see http://www.texasbirds.org/publications/bulletins/bulletin_vol_46_1_and_2.pdf#page=26). Teinert observed 2 significant mortality events. The first occurred with a snowfall event at Thanksgiving and the latter confirmed more mortalities during late-winter.

Figure 2. Bobwhite weekly survival during the 2007-08 winter based on Program MARK estimates from radiotelemetry data from the Rolling Plains (Fisher County), Texas (Source: Teinert et al., 2009).

The agents

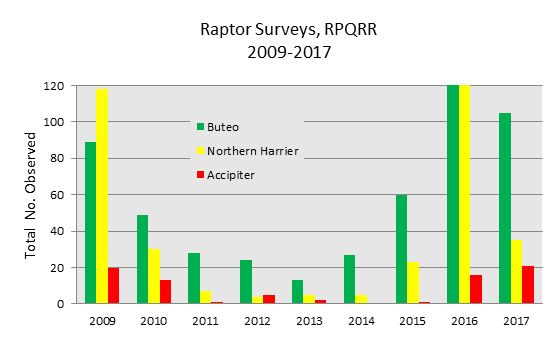

Raptors are one of the major predators for quail. This season there have been 29 confirmed raptor kills out of our 69 mortalities; that’s over 40%. Because they are such a major factor for our quail population we conduct raptor surveys twice a week. We drive a twenty mile route and identify birds of prey to their species. In 2016, our Northern Harrier and Buteo (Buteos include birds such as Red-tailed Hawks and Swainson’s Hawks) populations spiked, with an average of 10.22 raptors per survey. This spike corresponds with a spike in our small mammal and quail populations. The abundance of prey likely attracted the raptors—these populations ebb and flow. As our small mammal and quail populations have returned to more normal levels so have our raptor populations. In 2017 we averaged 4.13 raptors per survey.

Figure 3. Cause-specific mortalities of radio-marked bobwhite and scaled quail, RPQRR, Dec 2017 – Feb 2018.

Figure 4. Raptor trends at RPQRR, 2009 – 2017.

Accipiters include Cooper’s Hawks and Sharp-shinned Hawks. Accipiters are bird hunters (Dr. Rollins refers to them as F-16s; they’re designed for air-to-air combat). Despite the rise in other raptors, the number of accipiters remained relatively low, but our data for accipiters are likely biased low. Their elusive nature and tendency to perch in denser shrub cover, makes them more difficult for us to detect. Even with their low numbers, we suspect accipiters account for most of our quail mortalities. Buteos include the common red-tailed hawk (in Rollins’ lingo, the “B-17 bombers”) and northern harriers (“A-10 Warthogs”), target mainly small mammals but will opportunistically capture quail.

Déjà vu 1943

“Between then (17 Jan 1943) and January 15, the bobwhite population was disrupted with explosive suddenness, and all but remnants of coveys were lost, to predation. . . Everywhere the ground was littered with evidence that predation had been recent and terrific. Significantly, evidence of predation on scaled quail was light.” – A. S. Jackson (1947)

“Blue quail are somewhat more intelligent than bobwhites.” – V. Lehmann

In my opinion, harriers are underrated in their ability to catch quail. See Casey Weissburg’s excellent photo (above) of a harrier carrying off a leg-banded bobwhite recently. In an incident of a bobwhite irruption in King Co. terminated by predation in 1943, A. S. Jackson described the events leading up to and during the mortality event. This is an interesting read (and read the questions/comments he received after his presentation). He reckoned that harriers were the only raptor common enough to account for most of the predation events.

Feather piles

When someone calls me saying their quail population has “disappeared” I ask if they’ve observed any feather piles (i.e., evidence of predation) during their sojourns afield. They always answer “no.” If there has indeed been an implosion, shouldn’t one be observing feather piles? Since last month, I have solicited observations from quail hunters about the incidence of feather piles (i.e., kill sites) they observed while hunting. One serious hunter (Steve Snell, QM 2015, RPQRF board member) observed 20 such kill sites in 3 days of hunting in Borden Co. I find these numbers incredible (not that I doubt Snell’s count), but other hunters were also reporting feather piles commonly. Over the last two months of quail season, we’ve been saving pelts from the bobwhites harvested at RPQRR. Soon we’ll be placing those at random locations across the ranch to determine how long such feather evidence remains visible.

When someone calls me saying their quail population has “disappeared” I ask if they’ve observed any feather piles (i.e., evidence of predation) during their sojourns afield. They always answer “no.” If there has indeed been an implosion, shouldn’t one be observing feather piles? Since last month, I have solicited observations from quail hunters about the incidence of feather piles (i.e., kill sites) they observed while hunting. One serious hunter (Steve Snell, QM 2015, RPQRF board member) observed 20 such kill sites in 3 days of hunting in Borden Co. I find these numbers incredible (not that I doubt Snell’s count), but other hunters were also reporting feather piles commonly. Over the last two months of quail season, we’ve been saving pelts from the bobwhites harvested at RPQRR. Soon we’ll be placing those at random locations across the ranch to determine how long such feather evidence remains visible.

Prey situation

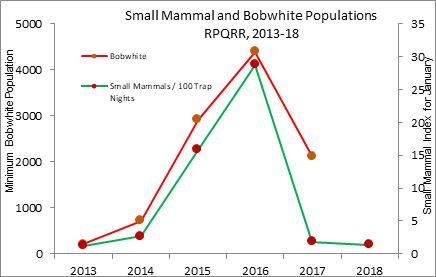

Figure 5. Small mammal abundance (green line) vs. Minimum Known Quail population (red line), RPQRR, 2013-2018.

As you can see, quail abundance and small mammal (i.e., rodent) abundance have tracked each other quite incredibly at RPQRR. The relationship of small mammals and quail is important because small mammals have the potential to serve as buffer prey for quail, or species that shift predatory pressure away from quail. Alternatively, high abundance of small mammals could also attract predators and the relationship of small mammals and quail demography could be antagonistic. Thus, it is important to understand the mechanisms of their relationship.

During small mammal trapping we trap in 8 habitat types. We set up five 50m x 50m grids, with 25 traps per grid. This totals to be 4,000 trap nights per session. Hispid cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus) comprised the majority of the trap yield in 2016, but experienced a 99% population decline in 2017. All small mammal species, except Mexican ground squirrels (Spermophilus mexicanus), exhibited lower numbers during the June 2017 trapping season. More Mexican ground squirrels (19 total) were captured during the June 2017 trapping season than all other trapping efforts combined. Interestingly, we identified ground squirrels (via photo surveillance of quail nests) as significant egg predators last summer.

This year our small mammal populations have continued to decline from the low population we observed in 2017. After checking 4,000 traps we only captured 55 individual rodents, 40% of those being wood rats (Neotoma). Cotton rats accounted for 97% of the rodents trapped in January 2017 . . . but not a single cotton rat was captured in January 2018. The dearth of rodents and the rise in quail mortalities are undoubtedly related. Considering the past relationship between small mammals and quail populations, we anticipate documenting future quail response to this drastic decline.

Coyotes and quail

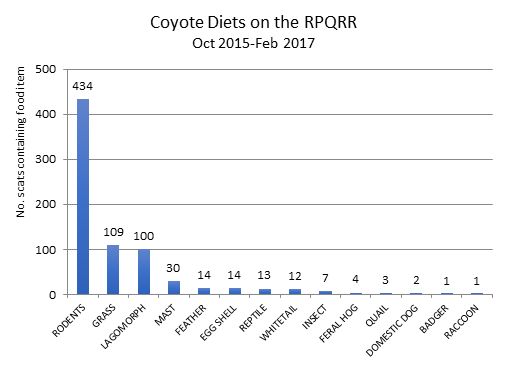

Coyotes are usually maligned as menacing predators of quail. Are they? Our data, based on scat content analyses conducted over 5 years (2010-12 [La Niña conditions; Tyson 2012], 2015-16 [El Niño conditions; Bowlin 2018]) have exonerated coyotes as an important predator of quail, at least here at RPQRR. Even though quail abundance varied greatly between these two studies, neither indicated significant predation on quail. Our diet studies have documented very low occurrence of quail (< 1%) in diets of coyotes whereas they prey on potential predators of quail (e.g., snakes, skunks) more than quail. Accordingly, we give them a pass. When you pass one along a ranch road, it will likely stand and stare at you from 50 yards away.

Figure 6. Number of coyote scats (n=496) containing particular food item (collected October 2015-February 2017) on the RPQRR, Fisher County, Texas. Quail were identified in only 3 scats (0.6%). Source: Bowlin 2018; MS Thesis, Texas Tech University.